Whence Quantum Fiction, Part Two

To understand the significance of Quantum Fiction, we must go back to the Nineteenth Century, to examine the rise of modern art:

MODERN ART AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Modern Art arose in part due to the revolutions in Europe beginning in 1848, but also in reaction to the invention of photography (1820s). Previously, painting and sculpture had been the primary means for wealthy patrons to preserve their images, through portraiture. Photography changed this, especially as photo salons became inexpensive and readily available (by the 1860s). New inventions such as fast film and portable or hand-held cameras began changing the way we saw the world, with a new type of super-accurate realism.

Eadweard Muybridge, Horse in Motion, 1878.

This technology undercut and threatened portrait painters. Photographers could do their jobs more cheaply and in minutes. The press of the day called photography “Painting with light.” Now we could record real events as they actually were, directly from nature, without the intermediary role of the artist.

The response to this threat was immediate and radical. If photographers could “Paint with light,” then painters must aim to “Paint light itself,” achieving through paint the removal of the intermediary of the photographer’s plate. Impressionism was born; with plein air painting, a much lighter and more vibrant palette, and a loss of photorealistic detail. Doing a job that photography could not equal.

Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise, 1872.

THE LIE OF FALSE REPRESENTATION

Simultaneous to this championing of the human element and sensations in art by the Impressionists, other artists began to exhibit work which began to challenge outmoded standards. Again, this was done via an appeal to a higher order of realism and a deconstruction of representation, depicting “what was” as opposed to “what seemed to appear.”

Quite famously, the art critic Henri Fouquier once denounced a painting by Édouard Manet, Portrait of Zola, saying, “The accessories are not in perspective, and the trousers are not made of cloth.” This invests a truth which seems obvious to us now, but was quite radical in the mid-19th century: The trousers are of course not made of cloth, but paint. (Arnason, 13)

Édouard Manet, Portrait of Zola, 1868.

POST-IMPRESSIONISM

Throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, new modern art forms evolved and continued to challenge traditional forms of representation: Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Pointillism, Symbolism, and Expressionism each posited a different view of reality than static, realistic photographs. Paintings no longer captured what could be seen (as a camera could), but strove to capture what could be derived, felt, experienced, examined, or even transcended.

As the twentieth century approached, new technologies and then scientific theories posed new challenges and pressures, encouraging art to move even further into experimentation. The invention of motion pictures (Lumière brothers, 1895) added the element of time (and perhaps) episodic story-telling to the milieu. Rather than reject this intrusion as it had photographic portraiture, modern art seemed to embrace the motion picture and the often garish makeup and costumery seen in the cinema. The result of this exploration was often simultaneously beautiful and disturbing; but always the story of events and the cinematic view was woven across the surface, sometimes rife with emotion.

Henri Toulouse-Latrec, At The Moulin Rouge, 1895.

This new technological excitement came at a time when society was celebrated as decadent, simultaneously vital and melancholy, and ultimately limited by its own temporality. The fin de siècle in Europe was a party without a particular goal or purpose, set to end when the clock struck zero. The inevitable happened, the key post-impressionists died, and art itself seemed to hang in the balance at a time when its imagination had just been invigorated.

RELATIVITY AND THE LOSS OF ELEMENTS OF REPRESENTATIONAL FORMS

We arrive at the “annus mirabilis,” 1905, and Albert Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity, which seemed a dream come true for modern art. Einstein turned the very universe upside-down with the assertion that the speed of light is constant, that time can “dilate” and length “contract.” The static nature described by the classic universe (and still a vital component of art) was exploded.

The art world saw its imagination run wild with the ideas of “New Physics.” Fauvism had already experimented with further breaking representation by using bright colors straight from the tube. The painting was arguably “of paint,” since realistic colors were no longer a consideration, even if approximate forms were retained.

Henri Matisse, La Danse, 1910.

In Paris, George Braque and Pablo Picasso began deconstructing form with cubism, which (usually) retained a realistic color scheme, distorting representation along a different axis than Fauvism:

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907.

Such Cubist works as Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) began to work on the transformation of recognizable forms by movement through space. These works were trying to represent the 4th dimension, spacetime, at the expense of realist representation:

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912.

In 1915 Einstein wrote his paper on General Relativity, which did away with Newton’s law of universal gravitation. The static nature of the universe, the very stage on which Picasso’s nudes stretched their limbs and Matisse’s nudes danced, was gone. It was now replaced by “spacetime,” which was relative and changing, and gravity was no longer a force in the classic sense but some “trick or illusion” resulting from the curvature of spacetime.

It seems like the reaction to this new announcement was immediate and palpable. Futurism began to embrace new technology, and, most notably, Expressionism finally did away with the representation of form entirely. In the next work, only the title gives any clue about what these colors and forms might portray, the vague organic figures and plant or fruit-forms which might derive from a cityscape or merely random imaginings from an afternoon spent in the artist’s loft:

Wassily Kandinsky, Moscow I – 1916 (1916).

At some point, almost quietly and simply, art finally abandoned its 15,000-year history with representation through form and color entirely, with Abstract Expressionism:

Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue #4, 1916.

These works are arguably not without “subject,” per se: Kandinsky expresses “Moscow” and O’Keeffe “Blue.” But we wonder in a relative sense what side of the canvas the meaning arises, and whether (with O’Keeffe in particular), part of the work’s meaning is supplied by the experiences of the individual viewer. We decide on the meaning, finally completing the circle of true expression began by Manet a half century earlier.

These were arguably the most “honest” works of art the world had ever seen, since they no longer attempt the magic trick described in the myth of Zeuxis and Parrhasius: They do not attempt to fool the observer.

This experimentation was not done by people who had any inkling of what Relativity or Quantum Mechanics meant. All they comprehended was that it was new, it did away with the “old view” of the universe, and it excited the imaginations of both artists and people who read newspapers. At its core, Theoretical Physics seemed forged in some curious alchemy; a by-now familiar scene of the theoretician hard at work, scribbling away indecipherable formulas on a blackboard:

Is it so strange, then, that at the very moment Einstein (and others) were positing something indecipherable to the public, painters like Kandinsky and O’Keefe were producing paintings without decipherable subject matter?

CRITICISM AND ACCEPTANCE

All of this experimentation stressed traditional forms of acceptance and criticism. How do we judge a work which is just a wash of blue paint on paper? Where no traditional form of representation is attempted? Who wins the contest when Zeuxis and Parrhasius’s contest is called off?

The answer is, we certainly don’t. From Manet’s example where the “trousers were not of cloth,” through to the twentieth century with abstract expressionism, criticism and acceptance have of necessity had to adapt to new forms of art. Modern art has successfully exercised cultural pressure back on its own means of acceptance. This has been done—slowly, in fits and starts—simply because the public sometimes preferred the variety of the new abstract forms. Critics had to adapt or become irrelevant.

Quite famously, at the very nadir of modern art, in 1863, the French Salon organized the Salon des Refusés, a type of conciliation to artists considered “too bad” to be hung in the regular exhibition. (The Salon rejected two thirds of the paintings submitted.) The public crowded into the Salon des Refusés, over a thousand visitors a day, initially to laugh at the displayed works. But they came, and paid admission. Because of its popularity, the Salon des Refusés was repeated in subsequent years, and by 1874 Impressionist works were admitted to the regular Salon. A revolution in art had occurred, and critics were convinced to change their judgment by popular demand.

An interesting sidenote: The Nazis attempted something similar in the 1930s, with ridiculous results. The government had confiscated thousands of works considered “degenerate” either because they were “insulting to the German people” (i.e., they were produced by Jewish artists, or Russians, on non-Aryans) or because they did not use classic representation (the Nazi regime preferred the clean, sterile lines of neo-classicism to illustrate its ideological dogma). In 1937 an exhibit was made of these confiscated works, Die Ausstellung "Entartete Kunst.” The show coincided with “The Great German Art Exhibition,” which housed the state-approved art.

As with the Salon des Refusés, the intention was to ridicule the “degenerate” art. People were supposed to laugh or be horror-struck. They certainly were, but they were also fascinated. The art was so different compared with the bland neo-classicism of the state-approved art that the exhibit drew over 2 million visitors, versus only 400,000 attendees for the “Great German Art Exhibit.”

The views of the critics of course did not change regarding this art, as the Salon had regarding Impressionism. Nor could it, because the judgement in Germany in 1937 was made by ideological distinctions rather than aesthetic: Disagreement with these meant courting imprisonment and death. But the popularity and success of the exhibit was a clear indication of the public’s tastes, and that modern art had established itself in way’s that ten years of enforced erasure could not undo.

Rather than admit their mistake, the Nazis embraced it. (After all, the millions of visitors of the Degenerate show had all bought tickets.) Additional Degenerate shows were organized yearly, right through the 1940s, when hardships of the war ended the experiment. In hindsight, it is generally accepted that the public was playing some kind of marvelous joke on the government that they never quite understood, but of course there is no evidence of this published in German reviews or newspapers of the time. The final net result of these shows was that modern art was preserved and curated in Germany, so some German modern art survived the war.

THE “1919 MOMENT,” AND THE BREAKING OF REALITY

Initially his General Theory of Relativity remained unproven, and some of the math involved used nonlinear equations which had to be approximated. More exact equations were completed by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916, but empirical evidence would not be gathered until 1919, by photographing a total solar eclipse.

The eclipse showed stars behind the sun not in their true position because of the warpage of space, by exactly the amount Einstein had predicted.

For modern art it was an astounding moment. Relativity had been something unseen, something you could not measure. It was a set of indecipherable formulas on a blackboard. The fact that most could not comprehend it was a bit of a joke. And suddenly, you could see it. With quite a simple (yet still incomprehensible) explanation: The stars in the photograph were not here but there.

The vindication of Einstein was also a vindication of something they had played with since the mid-19th century: Appearances can deceive. There might be a “truer truth,” as represented by the star’s “actual location,” which we cannot observe directly. Photography’s purpose - proven in 1919 - is to demonstrate that which is false. So art must strive to portray what photography cannot give us - that which is “true.” That had so far been done by moving away from representation, until all that is left is “paint.” This is the literal pathway, begun by Manet. But another way seemed possible: To unlock the individual observation and experience which lies within the human mind as an alternative to external reality.

SURREALISM AND THE CONTRADICTION

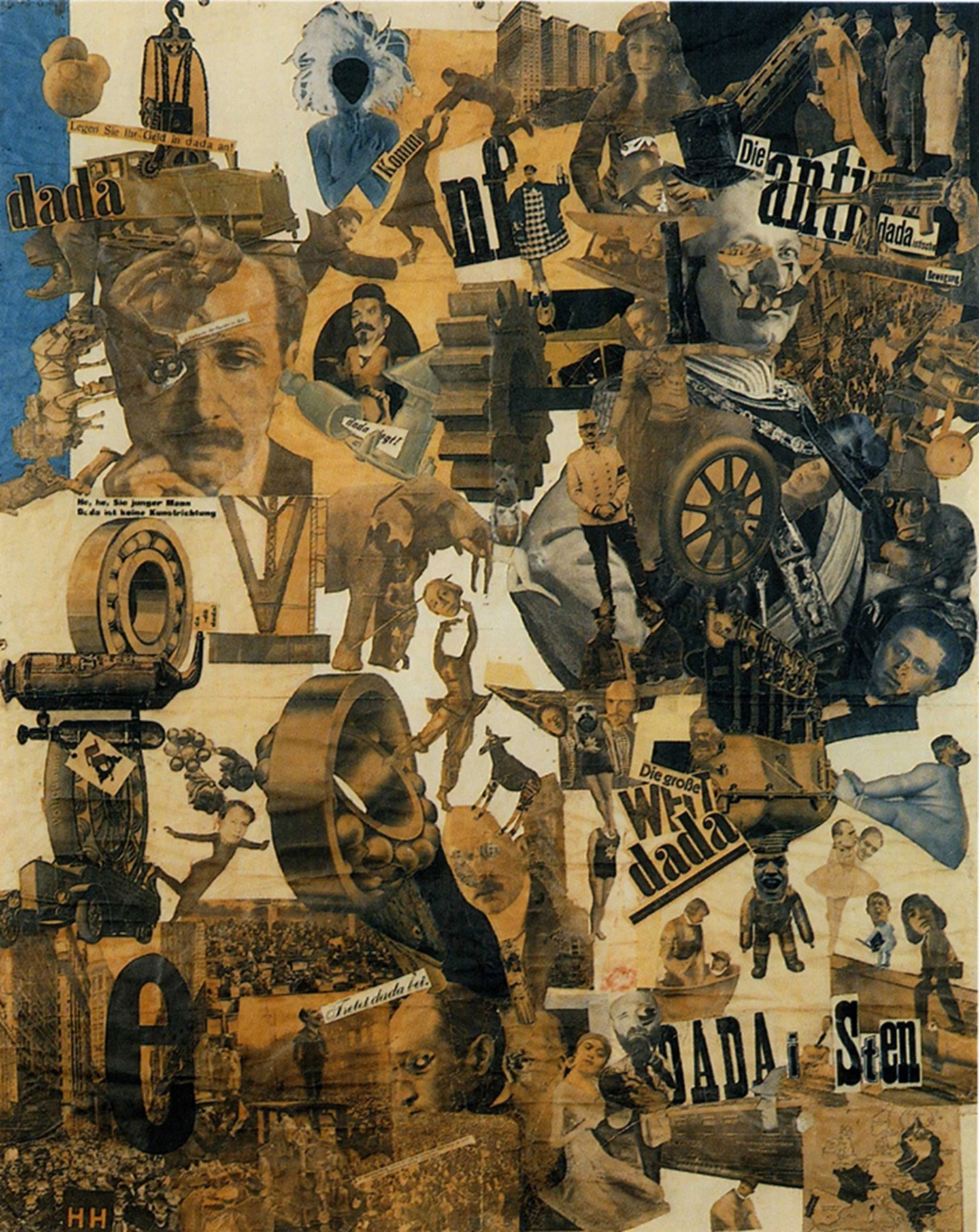

Art had already seen the return of recognizable imagery in mixed arrangements with Dadaism. (It had never really left. The Abstract Expressionists were attention-getters, but still in the minority.) This was art made in protest of World War I, and at its core lay the idea that the world (perhaps the entire universe) was absurd. It was a joke. This type of social commentary always relies on recognizable imagery, public figures and machinery, here with a collage arrangement adapted from Synthetic Cubism:

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Epoch of Weimar Beer-Belly Culture in Germany, 1919.

As the war ended, so to the need to tell this joke, so Dada was short-lived. The idea of absurdity remained however, and was expanded by an international group of artists called the “Surrealists.”

The Surrealists saw the world as broken and contradictory, even down to its fundamental order. (Perhaps picking up on the implied contradiction of Relativity, of a star that could “appear” in the wrong place.) To illustrate the contradiction, to lay it bare, they illustrated recognizable forms in the same “random” arrangement as Dada had. But Dada expressed a relationship between all the items. (An absurdity, yes, but still a meaning, apparent to any observer who could recognize the public figures and machines appearing in the collage. A code which may be lost to us now, but apparent to anyone living in Zurich right after the war.) For Surrealists, there WAS no logical relationship between the items, because all meaning was lost in the contradiction between the waking world, bound by logic, and the dream world, which was ruled by pure thought. The picture literally becomes an illustration of a thought, or a dream.

Joan Miro, Horse, Pipe and Red Flower, 1920.

For some the absurdity was a stark contrast to the uselessness of Dadaism. By the power of imagination, an ordinary individual could work out the contradiction for themselves, and therefore explore dream states and the nature of thought, a process that implies a functional role for the work of art. Unlike O’Keeffe’s Blue #4 (pictured above) which might or might not lead to any revelation on the part of the observer, there is a suggestion we must learn something by contemplating Surrealist works; the precise nature of that something is not implied, only that it is within us and unlocked by imagination.

The natural culmination of the dream state, again, eventually led to a loss of recognizable imagery. But this is not abstract work; it clearly pictures something. What these figures might mean or be is supplied mostly by the observer, as in any dream scape.

Joan Miro, The Hunter (Catalan Landscape) 1923-24.

It is as if Miro has unlocked the final key in our unconscious: Quantum Mechanics, conceived in 1900 by Max Planck and running a footrace with Relativity as an alternative contradictory explanation for observed events since 1905, finally found its expression in Surrealism. A literal event-map description of this painting could be a work of Quantum Fiction. It is a field of contradiction: We are dreaming, yet we are awake. The things we see have meaning but they do not. There are no rules but there is a precisely defined relationship between everything, something we can measure. The stars behind the sun should be there but they are over there. Reality itself is an implied contradiction that we must reflect mightily upon in order to fully comprehend.

SUMMARY OF PART TWO

Photography posed a challenge to portrait artists in the mid-nineteenth century, threatening their livelihood. The response was the invention of new art forms that photography could not replicate. Over the next eighty years, these new art forms grew and evolved. Part of this evolution was inspired by political upheavals of the time (such as the revolutions of 1848, Marxism, and World War I). But part of it was inspired by technological advances and especially by advances in theoretical physics.

Impressionism went outdoors and “painted light.”

Post-Impressionism started to challenge the representation and rendering of realistic form.

Fauvism discarded traditional color palettes.

Cubism deconstructed organic forms entirely.

Synthetic Cubism depicted forms moving through time and incorporated collage.

Expressionism broke entirely with traditional form and color, presenting paintings almost devoid of subject.

Abstract Expressionism presented works entirely devoid of subject.

Dada used collage and found objects with recognizable form to make a political protest.

Surrealism depicted an alternative dreamscape and depicted a contradictory universe.

These new art forms (and many others) have been called “Modern Art.” Collectively, they can be seen as an evolutionary response to the challenge posed by photography. We moved away from painting “things as they appear” to painting “things as they are,” an exploration which has included ideas of theoretical physics and imagination.

Next, in part three, we will explore twenty-first century implications of why this exploration may be still ongoing.

Bibliography:

Arnason, HH – Realism Impressionism and Early Photography (Ch.02), recovered from https://www.scribd.com/document/311834582

Breton, André, Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924. Recovered from chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www2.hawaii.edu/~freeman/courses/phil330/MANIFESTO%20OF%20SURREALISM.pdf

Loomba, Sahil, The False Mirror: On the Functional Inytent of Art, (2017), recovered from https://sahilloomba.medium.com/the-false-mirror-4191e1aaf92d.

ML Musee Du Luxembourg, The Genesis of Cubism and Painting in Literature, recovered from https://museeduluxembourg.fr/en/actualite/la-genese-du-cubisme-en-peinture-et-en-litterature.

The Art Story, Surrealism, recovered from https://www.theartstory.org/movement/surrealism/